The Why of Warburg: why cancer cells choose growth over energy.

It's all very well knowing what the Warburg is— understanding why your cells are changing lanes is the key to recovery.

The Warburg effect is all the rage in cancer circles. This year I’ve heard multiple pronunciations (it’s VAR-burg) and explanations ranging from botched to bonkers to brilliant, but I haven’t heard anyone explain why it happens. And without that understanding there’s not a lot of point in knowing how it works.

I’m not being dismissive of anyone’s attempt to grapple with complex biochemistry – I’m still doing that myself, always aware that career biochemists might be sniggering. But our ability to share complex biochemistry is pointless if it doesn’t actually get to the point. So today, I want to put that right, at least as far as Warburg is concerned.

The Man Behind the Effect

I first stumbled across Warburg and his Effect in 2012, after reading Thomas Seyfried’s groundbreaking book on cancer metabolism. Warburg was, as I’m sure you know, a German-Jewish scientist of notable genius, who lived in dangerous times. Working as a biochemist in Berlin in the 1930s, he understood the dangers of smoking, pollution and fertilisers, along with the benefits of B vitamins, long before the rest of us. He generously mentored other brilliant minds, including Hans Krebs, and counted Einstein among his family friends. In seeking to unravel the mysteries of human biochemistry he developed a unique way to measure gases from microscopically thin slices of animal tissue - a technique that changed the face of science.

Using this method he discovered that the cancer cells he was studying were respiring anaerobically even in the presence of oxygen, a discovery that won him a Nobel Prize in 1931. This was a major leap in understanding that cancer cell metabolism is abnormal. If only his work had extended to looking for other cell types that might do the same thing, or if German politics had not taken a turn for the worse, the history of cancer might have been completely different.

My Own Journey with Warburg

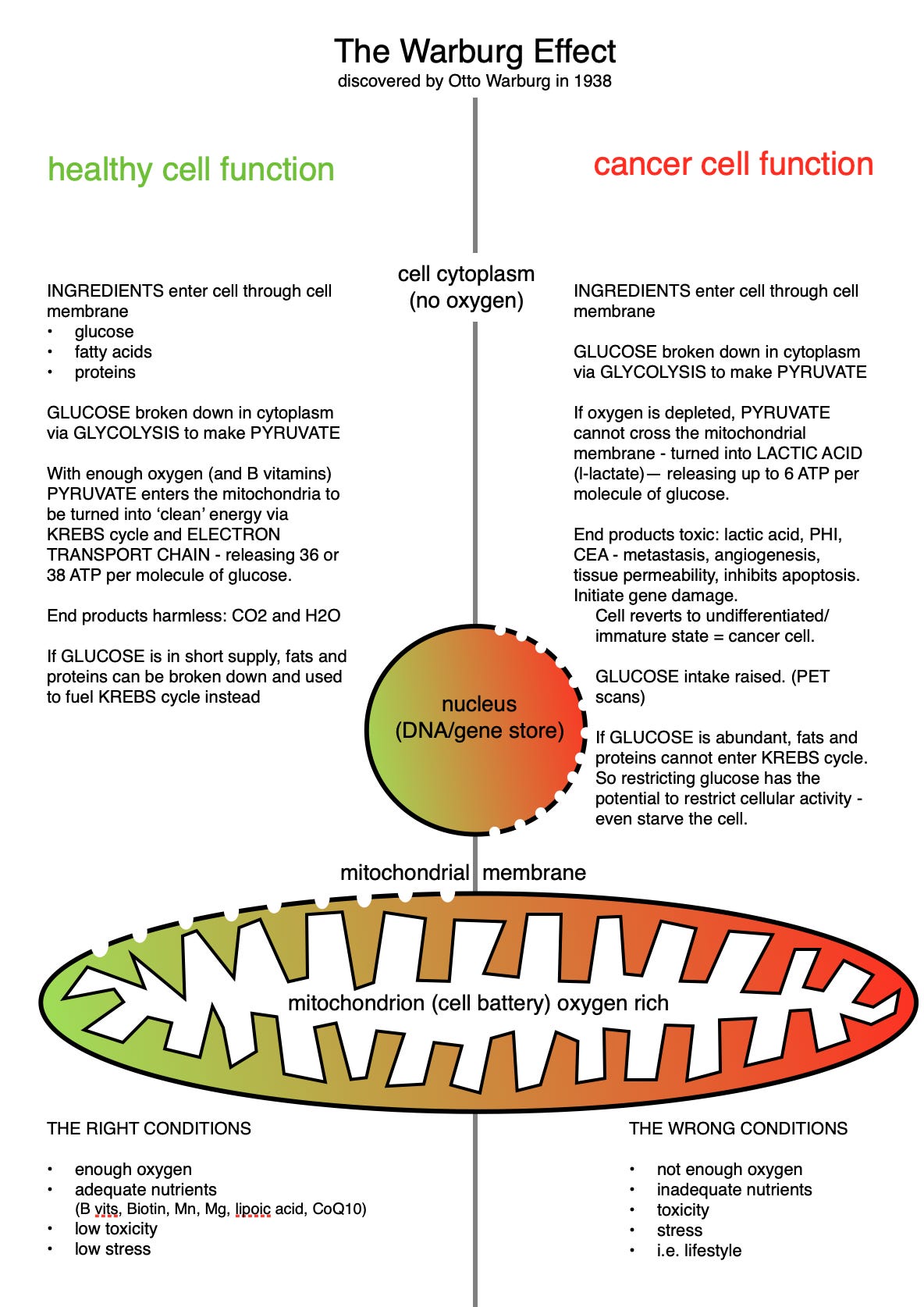

My own early attempts to explain Warburg were mostly accurate but woefully incomplete. To show you what I mean I’m sharing below a graphic I produced for a workshop on the metabolic approach to cancer in 2015. (Yes, I’ve been doing it for a long time). Not only has my diagrammatic ability improved 😅, my understanding of Warburg has been revolutionised. Back then, I hadn’t fully understood the point either.

These days, while acknowledging his great mind and staggering work, it pays to look at his theory with a more curious eye. The key to criticising any scientific theory is to examine the assumptions. And the route to a deeper understanding of Warburg is to question the assumption that cancer cells are damaged.

Genuine curiosity is a vital quality for every scientist - one that sits uneasily alongside the schoolroom desire to put up our hands and say, ‘I’ve got the answer!’ Those of us keen to push the boundaries of this important healing work have a duty to our profession and to our patients to do the deep, hard work necessary to fully understand the methods we are endorsing, without jumping to conclusions. When I first read about the Warburg Effect, I thought, “Job Done. Now we have a cure for cancer and we can all get on with our lives.”

Not so fast.

The Plot Thickens

Thanks to the miracle of modern research, and to the healthy scepticism and eternal disdain of scientists for each other, experiments carried out over the past decade have shown that, while the Warburg Effect is associated with cancer cells, it’s not all cancer cells, and not all of the time.

Sound familiar? That’s the same criticism that’s levelled at the Somatic Mutation Theory of Cancer - not all cancer cells contain genetic mutations. They’re tricky blighters these tumours!

As I write this in August 2025, The Metabolic Approach to Cancer is having a day in the sun. There is excitement in the air as we dare to hope that integrative oncology might be here to stay. But we are also at risk of squandering the opportunity if we share misinformation, even if it is based on a burning desire to change the face of oncology and provide more choice for patients. As a group, we have collectively challenged the evidence for the genetic approach for well over a decade; we need to make sure that the way we explain the metabolic approach is not similarly flawed. Otherwise we risk losing our newly minted and hard won credibility – and proving the eye-rolling medical profession right.

To move forward as a credible group, we have to acknowledge that we all have a lot to learn and weave that into the way we communicate. We have to share what we know, admit what we don’t and avoid muddying the waters. We must bring our ideas and research into the light after careful consideration, along with a dollop of scepticism and a side of humility. And we have to tread carefully in areas we don’t fully understand, where the science is not yet fully elucidated. Lives are at stake.

My own (doubtless still incomplete) understanding of the Warburg Effect was boosted immeasurably by reading the research of Nick Lane - again and again and again - and it is on the shoulders of his work that I want to share “The Why of Warburg” today.

This is the first of a 3-part series that will explain first why Warburg is not a mistake or a malfunction, then go on to explain why it happens and, lastly, discuss what we need to understand to stop it happening.